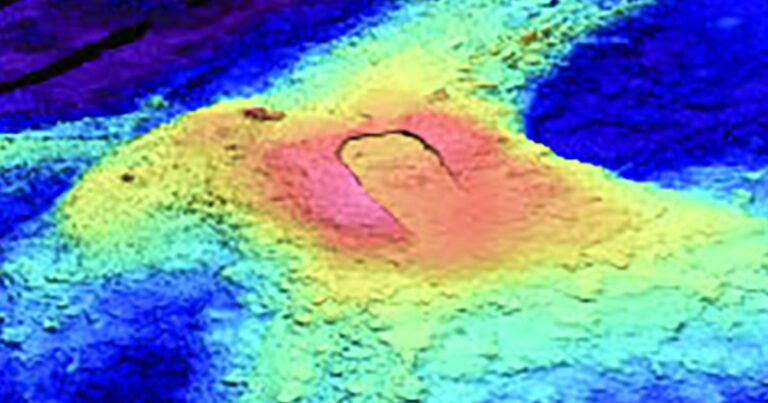

A subaquatic volcano, about 300 miles from the Oregon coast, appears to be coming back to life.

Scientists who have been monitoring the vast submarine volcano for decades say they are ready to erupt from recent activity, including an increase in earthquakes nearby and swelling in the structure itself.

Bill Chadwick, a volcanologist and research professor at Oregon State University, predicts that between now and the end of the year, the volcano known as Axial Seamount could erupt any time between now and the end of the year.

Chadwick and colleagues at the University of Washington and the University of North Carolina Wilmington use networks of submarine sensors to eavesdrop on volcanoes.

Over the past few months, the instrument has picked up clues that the sailors on the shaft are upset. For example, between late March and early April, researchers recorded more than 1,000 earthquakes per day. The volcano is also steadily expanding and is a clear sign that it is filled with melted rocks, Chadwick said.

“This volcano resembles a Hawaiian volcano that erupts highly fluid lava,” he said. “They tend to expand like balloons during eruptions. On the axis, the seabed is actually rising, and that's a big signal.”

However, unlike some of Hawaii's volcanoes, there is no real danger to humans if the sailors on the shaft are blown away.

In addition to being hundreds of miles offshore, the peak sinks to about a mile deep in the water. The volcano is far enough that even strong eruptions cannot be detected on land.

“There's no explosion or anything, so it's not going to really affect people,” Chadwick said. “If you were on a boat across the sailors while it was erupting, you probably never know that.”

But that doesn't mean that the eruption is not a grand event. Researchers say that the last eruption of Axial Seamount in 2015 saw enormous amounts of magma pour from the volcano.

“For reference, it's about two-thirds of the height of Seattle's space needle,” Chadwick said. “It's a lot of lava.”

Axle seafarer formed in what is known as a hot spot. A melted rock plume rises from the Earth's mantle to the crust. This geological process is not uncommon. Hotspot volcanoes dot the seabed, and some create chains of islands like Hawaii and Samoa. What makes the Axial Seamount unusual, however, is its lie on the boundary between the Pacific and Juan de Fuca plates. Plate separation, and the resulting pressure beneath the seabed, always fuels volcanic activity and produces fresh oceanic crust in the area.

Chadwick has been tracking his activities at Axial Seamount for the past 30 years. Over that period, the volcano erupted three times in 1998, 2011 and 2015.

As he and his colleagues wait for an imminent eruption, they are testing whether repeated patterns of activity in the axis sailors can produce reliable predictions when an underwater volcano falls off.

But eruption prediction is notorious business. Volcanoes can behave in unpredictable ways, and depending on the type, they can show very different warning signs.

“They're making the most of the world,” said Scott Nooner, professor of geophysics at Wilmington University, North Carolina. “I don't know if it's still erupting or how magma moves beneath the surface of the Earth.”

Scientists have been successful to some extent with short-term predictions (usually just a few hours before the eruption) that will help local officials decide whether to evacuate the area or take other precautions. However, long-term forecasts remain difficult.

That's why, according to NOONER, axial seafarers for purification tools for eruption predictions, make such a good natural laboratories.

“On land, you predict that a volcano will erupt in a week or a month, and if you're wrong, you'll sacrifice a lot of money, time and worries to people,” he said. “But these eruptions don't affect anyone, so there's no need to worry about it with axle seafarers. So it's a good way to test models, test predictions and hold them accountable, but they don't have the same impact as volcanoes on the land.”