Mark pointingClimate and Scientific Reporter, BBC News

BBC

BBCWhen Matthias Hass first visited the Rhone Glacier in Switzerland 35 years ago, the ice was a short walk from where his parents parked their cars.

“When I first stepped onto the ice… there was an eternal special feeling there,” says Matthias.

Today it's 30 minutes from the same parking lot and the scene is very different.

“Every time I go back, I remember how it was,” recalls Matthias, now director of Glacier Monitoring in Switzerland (Gramos), recalling “what glaciers looked like when I was a child.”

As these frozen ice rivers retreat, there are similar stories on many glaciers all over the globe.

In 2024, glaciers outside the giant ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica lost 400 billion tonnes of ice, according to a recent report by the World Weather Organization.

This corresponds to a block of ice, 7 km tall (4.3 miles), 7 km wide and 7 km deep. It's enough water to fill the 180 million Olympic pool.

“Glaciers melt everywhere in the world,” says Professor Ben Marzion of the Geography Institute at the University of Bremen. “They are sitting in a climate that is very hostile to them now due to global warming.”

Swiss glaciers have been particularly badly hit, losing a quarter of the ice in the last decade, a reading from Gramos revealed this week.

“It's really difficult to grasp the scope of this melt,” explains Dr. Huss.

But, photographs – from the universe and the ground – tell their own stories.

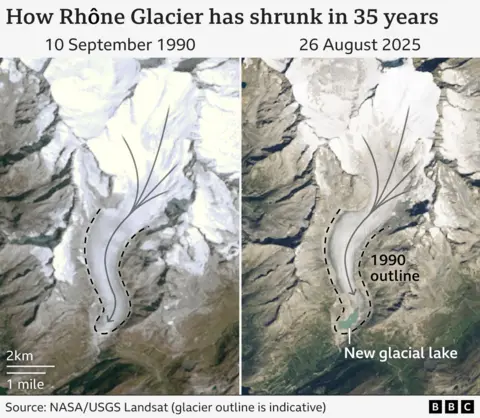

Satellite images show how Rhône Glacier has changed since Dr. Huss' first visit in 1990. In front of the glacier is a lake where it once had ice.

Until recently, glaciologists in the Alps thought 2% of the year were lost as “extreme.”

Then, 2022 blew that idea out of the water, with almost 6% of Switzerland's remaining ice being lost in a year.

Following this, there were also major losses in 2023, 2024 and now 2025.

Regine Hock, a professor of glaciology at the University of Oslo, has been visiting the Alps since the 1970s.

Her lifelong change is “really amazing,” she says, but “what we're seeing right now is really a huge change within a few years.”

The Clariden Glacier in northeastern Switzerland was largely in balance until the second half of the 20th century. They had fused as much ice as they melted, and they had acquired as much ice as they melted.

But this century, it is melting rapidly.

For many small glaciers like the Pizol Glacier in the Northeast Swiss Alps, it was too much.

“This was one of the glaciers I've seen and is now completely gone,” says Dr. Huss. “It definitely makes me sad.”

Photos allow you to go back in time.

Grease Glacier, located in southern Switzerland, near the Italian border, has retreated to about 2.2 km (1.4 miles) in the past century. Where the end of the glacier once stood is now a large glacial lake.

In southeastern Switzerland, glaciers once fed on the large Morterach Glacier, which plunged towards the valley. The two of them are no longer meeting now.

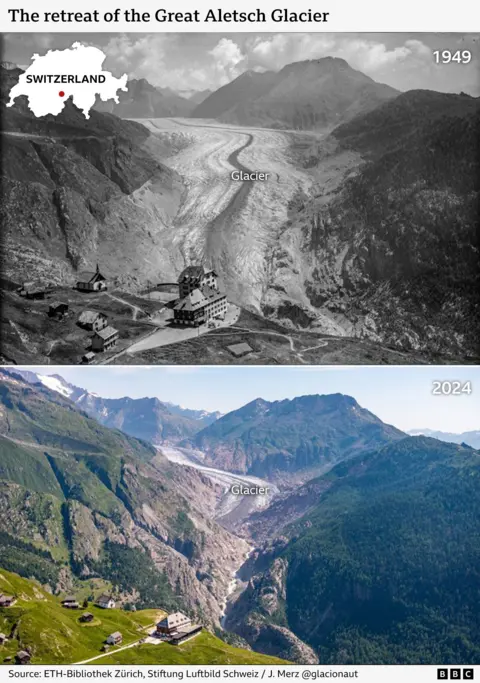

And Great Aletch, the largest glacier in the Alps, has retreated after about 2.3km (1.4 miles) in the last 75 years. Where there was ice, there is now a tree.

Of course, glaciers have grown naturally for millions of years and shrunk.

Cold snaps of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries – part of a small glacial age – glaciers progress regularly.

During this time, many were thought to be cursed by the demons of alpine folklore.

There are even stories of villagers who ask villagers to talk to the glacier spirits and move the mountains.

The glacier began retreating extensively across the Alps around 1850, but timings vary depending on where.

It coincided with increasing industrialization when the combustion of fossil fuels, especially coal, began to heat our atmosphere, but it is difficult to unleash the time-consuming natural and human causes.

If there is no real doubt, it means that particularly rapid losses over the past 40 years or so are not natural.

Without humans warming the planet – the glacier is expected to be nearly stable by burning fossil fuels and releasing enormous amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2).

“This can only be explained when CO2 emissions are taken into consideration,” confirms Professor Marzeion.

What's even more calm is that these large, flowing ice bodies take decades to fully adapt to the rapidly warming climate. This means that even if global temperatures stabilize tomorrow, the glacier will continue to recede.

“Most of the future melts in the glaciers are already trapped,” explains Professor Marzeon. “They are slowing down climate change.”

But everything is not lost.

According to a study published this year in the journal Science, if global warming limits the “pre-industrial” level of the late 1800s to 1.5c above, half of the ice remaining across mountain glaciers around the world can be preserved.

Our current trajectory is leading us to warming of around 2.7°C, above pre-industrial levels by the end of this century.

That excess water enters the river, ultimately meaning that the oceans are high in coastal populations around the world.

However, ice loss is particularly keen by mountain communities that rely on freshwater glaciers.

Glaciers look a bit like giant reservoirs. They collect water as snowfall during cold, wet seasons, turn into ice and release it as meltwater during warmer periods.

This meltwater helps stabilize the river flow during the hot, dry summers until the glacier disappears.

Its water resources losses have a knock-on effect on all people who rely on glaciers – irrigation, drinking, hydroelectric power, and even transport.

Switzerland is not immune from these challenges, but its meaning is much more profound for Asian alpines, with some calling it the third pole due to the amount of ice.

Around 800 million people rely at least in part on glacier meltwater, especially for agriculture. This includes the Upper Indus River Basin, which serves parts of China, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

In areas with dry summers, meltwater from ice and snow can be the only important water source for months.

“That's where we see the biggest vulnerability,” says Professor Hock.

So, how do scientists feel when they face the future outlook for glaciers in the world of warming?

“It's sad,” says Professor Hock. “But at the same time, it also gives us power: carbonization and reducing the (carbon) footprint, and we can preserve the glacier.

“We have it in our hands.”

Top image: Tschierva Glacier, Swiss Alps, 1935 and 2022. Credits: Swisstopo and Vaw Glaciology, Eth Zurich.

Additional reports by Dominic Bailey and Erwan Rivault.