Suranjana TewariAsian Business Correspondent, Tokyo

BBC

BBCLast year, more than 18,000 elderly people with dementia left home and wandered in Japan. Approximately 500 people were later found dead.

Police say the number of such incidents has doubled since 2012.

According to the World Bank, people aged 65 and over now make up nearly 30% of Japan's population, the second highest percentage in the world after Monaco.

The crisis is further exacerbated by a shrinking workforce and strict restrictions on foreign workers coming to Japan for care.

The Japanese government has identified dementia as one of its most urgent policy issues, with the Ministry of Health and Welfare estimating that dementia-related medical and social security costs will reach 14 trillion yen ($90 billion, £67 billion) by 2030, up from 9 trillion yen in 2025.

In its latest strategy, the government signaled a stronger pivot to technology to ease the pressure.

Across the country, GPS-based systems are being deployed to track wanderers.

Some regions offer wearable GPS tags that can alert authorities the moment a person leaves a designated area.

In some towns, convenience store employees receive real-time notifications. It's a kind of community safety net that can find missing people within hours.

Robot caregivers and AI

There are also technologies aimed at detecting dementia early.

Fujitsu's aiGait uses AI to analyze posture and gait patterns to detect early signs of dementia, such as a limp while walking, slow rotation, or difficulty standing, and generates a skeletal contour that clinicians can see during routine exams.

“Early detection of age-related diseases is important,” says Fujitsu spokesperson Hidenori Fujiwara. “If doctors can use motion capture data, they can intervene earlier and keep people active longer.”

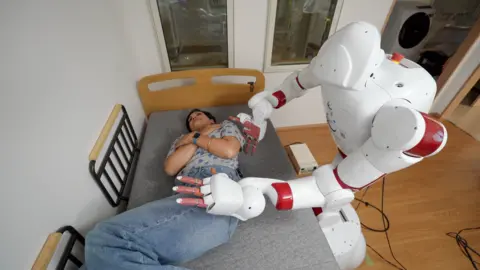

Meanwhile, researchers at Waseda University are developing AIREC, a 150kg humanoid robot designed as a “future” caregiver.

It helps you put on socks, make scrambled eggs, and fold laundry. Scientists at Waseda University hope that in the future AIREC could be used to change diapers and prevent pressure sores in patients.

Similar robots are already being used in nursing homes to play music and teach simple stretching exercises to residents.

They also keep patients under their mattresses at night to track their sleep and condition, reducing the need for human rounds.

Humanoid robots are being developed for the near future, but Associate Professor Tamon Miyake says it will take at least five years before robots can safely interact with humans due to the high level of precision and intelligence required.

“We need whole-body sensing and adaptive understanding – ways to adjust to each person and situation,” he says.

Emotional support is also part of driving innovation.

Poketomo is a 12cm tall robot that can be carried around in a bag or placed in a pocket. It reminds users to take their medication, teaches them how to prepare for the weather outside in real time, and provides conversation for people who live alone. This can help alleviate social isolation, the creators say.

“We are focused on social issues and working on using new technology to solve those problems,” Miho Kagei, Sharp's development manager, told the BBC.

Although devices and robots offer new ways to assist, human connections remain invaluable.

“Robots should complement human caregivers, not replace them,” said Miyake, a scientist at Waseda University. “They may take over some tasks, but their primary role is to support both the caregiver and the patient.”

People flock to the “Order Wrong Restaurant'' in Sengawa, Tokyo, founded by Akiko Kanna, seeking services for dementia patients.

Inspired by her father's experience with the disease, Khanna wanted a place where people could stay engaged and feel a sense of purpose.

Toshio Morita, one of the cafe's staff, remembers which table ordered what by using flowers.

Despite his cognitive decline, Morita enjoys socializing. For my wife, the cafe provides a place of respite and helps her continue working.

Khanna's Café shows why social intervention and community support remain essential. Technology offers tools and relief, but what truly supports people living with dementia is meaningful engagement and human connection.

“To be honest, I just wanted a little extra money. I like meeting all kinds of people,” Morita says. “Everyone is different, and that’s what makes it fun.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAdditional reporting by Jaltson Akkanath Chummar